22nd February 2022

There are over 600,000 teachers in the UK and nearly 250,000 higher education staff — a huge number of people, all in a highly responsible position. In these times where many young people’s lives are often being negatively affected by social media, we need to ensure that the people they trust are not making things worse due to their own online activities and published opinions.

Senior academics at universities have been known to bring their employers into disrepute due to their online social activities and connections as well as their offline behaviours reported in online news media. Usually, news outlets leave a permanently damaging online record of incidents deeming it to be of public interest. This affects students and institutions alike — sometimes dramatically.

During February 2022 SP Index carried out a study to understand how many universities have been affected by adverse media as a result of the behaviour of senior academics, the primary cause of such incidences, and the ensuing actions and outcomes.

Read on to find out what we discovered.

BACKGROUND

Universities are becoming more and more aware of the potential harm to students and wider society as a result of the educational influence imposed by its front line teaching staff, as well as the potential damage to its reputation and funding streams caused by undesirable behaviours of these same staff.

Lecturers and professors are given the hugely important role of making the world a better place by providing transformative education for students and to turn their curiosity and aspiration into a lasting basis for success and positive social impact. But what if these influential roles are involved in networks aimed at harming society or have beliefs or behavioural traits which do more harm than good?

Universities must be more careful than ever before if they are to recruit only the highest standard of teaching staff (their “Magister Optimus”) — those without hidden agendas, discriminatory viewpoints, religious or racial bias for example. In this regard, the background screening industry has been supporting the education sector for many years by providing a variety of checks and services. Looking to the future, more can be done — and more is necessary.

Societal pressure group demands, the Online Safety Bill and the recent enhanced guidance on safer recruitment from the DfE, are just a few examples where social online presence (Social Media Checks or OSINT Checks in vetting industry terminology) is likely to become a key ingredient in making the right staff selections going forward.

Online learning and the sharing of academic findings through the internet is now commonplace, and most professors and lecturers present themselves online in the very best light. However, the occasional public faux pas on sites such as Twitter and Instagram and the ease in which real life incidents can be reported so widely and quickly through online apps (the ‘internet’ being the judge and jury) can often mean that damage is done faster than you can say “Meta”.

SCOPE

The Office for Students lists over 130 Universities in the UK (excluding Higher or Member Education Institutions), and in the US the equivalent number is more than 5,000.

SP Index randomly selected 17 universities from each of the UK and US TOP 30, and using its smart-search technology was able to identify online adverse media reports for 100% of those sampled (all 34 universities).

All incidences were linked to senior academics and leaders whose behaviours and comments either online or in real life had been found worthy of media attention and online discussion, and for each incidence the university (their employer) was compelled to take action.

At first glance it may seem that a sample of only 34 universities is low and therefore not representative of the total education sector. However, given that not a single university from what is a randomly selected sample >57% of the top 30 universities in each country was without incidence, there appears to be a strong indication towards this being an industry trend.

Department for Education

The latest proposed update to the Department for Education’s ‘Keeping Children Safe in Education’ document, which covers safeguarding within schools and colleges, includes enhanced guidance on Safer Recruitment.

UK Government Guidelines

The UK government recognises that a DBS check and a couple of references are no longer enough when it comes to recruiting lecturers and teachers. The new proposals state that “schools and colleges should consider carrying out an online search (including social media)” — recognition that the best way to research an individual’s suitability for such an important post is to look into their online presence.

Recommendations

SP Index was formed in 2012 to support employers to further vet candidates based on their online profiles, in a structured and compliant way.

To minimise risk, the vetting industry recommended standard for educational institutions is to perform both an online Social Media Check and an Adverse Media Check for all senior academics and leadership roles.

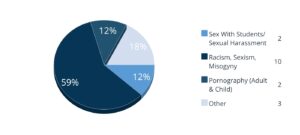

Behaviours UK

17 Universities were randomly selected from the Top 30 in the UK as listed by UNIPAGE.

For 100% of the universities selected, adverse news & media reports could be identified online.

Nearly 60% of online reports involved incidences of racism, sexism and misogyny.

Other reported incidences involved transphobia, antisemitism, homophobia, child pornography, and paedophilia.

All incidences occurred within the past 3 years.

Outcomes UK

The outcome in the majority of incidences (35%) was for the academic to resign. This aligned closely with the combined total number who had been fired or suspended.

On only 1 occasion was the staff member cleared of any wrongdoing following an investigation.

Investigations continue for 24% of the incidences.

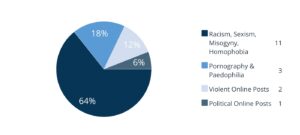

Behaviours US

17 Universities were randomly selected from the Top 30 in the US as listed by UNIPAGE.

For 100% of the universities selected, adverse news & media reports could be identified online.

64% of online reports involved incidences of racism, sexism and misogyny or homophobia.

Other reported incidences involved pornography, paedophilia, and violent or political online posts.

All incidences occurred within the past 3 years.

Outcomes US

The outcome in the majority of incidences (41%) was for the academic to be fired with a further 35% suspended.

18% of the incidences were in the process of being investigated.

Only 6% had resigned their post and no-one had been cleared of wrongdoing.

Impact Assessment

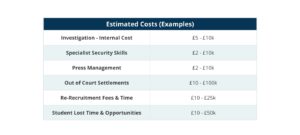

The damage caused by these incidents is difficult to quantify, but can certainly run into 6 digit figures (see below). It should be considered from the perspective of both commercial loss and damage to brand (somewhat overlapping), and affects the student and university alike.

Students give great consideration to where they should invest those significantly priced course fees — an investment made with the expectation that payback will come for many years into the future. Do they really want their alma mater linked to permanently stamped online content “wasn’t that the Uni with the racist professor who got sacked” or “the one with the lecturer accused of sexual harassment?”.

The universities to which these students hand over their academic faith and money carry a huge responsibility to deliver the best possible education and to protect the students’ investments — past, present and future.

When incidences occur, the university may well lose or temporarily have frozen the funding from private companies or government departments until matters are concluded and incidences have been dealt with.

Disciplinary processes and investigations are expensive and can often take a long time. Online incidents might require specialist cyber security skills to be contracted in for the investigation.

And then there are the costs of being ‘suspended on full pay while under investigation’ or out of court settlements to ‘walk away’ — after all, the damage to brand has already been done.

In short, once an incidence occurs, a domino effect can quickly establish itself pushing the PR, investigation costs and cost to resolution higher and higher.

CONCLUSION

It’s clear from our sample and the online intelligence we uncovered that universities both in the UK and US are suffering with a problem. 100% of our sample proved to have detrimental online content available for all to view (possibly permanently), some incidences being of a very serious nature. This will undoubtedly lead to lost revenues and ongoing reputation damage.

The differences in culture and employment legislation between the UK and US might explain the significantly higher US rates for those either fired or suspended, but what is obvious is the incredibly low number of those cleared of any wrongdoing.

Vetting the online connections and behaviours of academic staff (before, during and on exit) should surely be an inherent part of today’s people management processes to protect the brands, reputations and future revenue streams of both students and universities alike, as well as providing protection towards resources and assets.

The thing about online intelligence for employment vetting is that information is easily and readily available via independent companies such as SP Index and has been available for more than a decade. Applying specialist technology, online navigation expertise, and structured processes and procedures would allow universities to better achieve their objectives in a compliant, affordable and effective way.

So, why are so many still not adopting such readily available tools to combat the future risks?

Maybe a change to the risk attitudes of these institutions seems an obvious way forward.

Financial Analysis

Let’s just assume (conservatively in our view) that due to the high profile nature of many of the incidences, the average cost to students and the college combined was only around £50,000 (see table below). In our sample alone, this would equate to more than £1.5m for those fired, suspended or under investigation.

With over 130 institutions in the UK and over 5,000 in the US, the total cost of dealing with these incidences must be phenomenal.